Surrendering to creation

- jurigol

- Jul 3, 2025

- 4 min read

It’s not easy to speak about oneself.

We’re told it’s vanity, unnecessary exposure,

an inflated ego.

But if we look closely, we’ll see that this silencing

has a history.

It has a method.

The dominant structure — patriarchal, colonial, capitalist —

doesn’t want women as authors of their own narratives.

It wants us to repeat.

To reproduce what has been given.

And yet, when a woman begins to organize her own experience into

language, something slips out of control.

It becomes political.

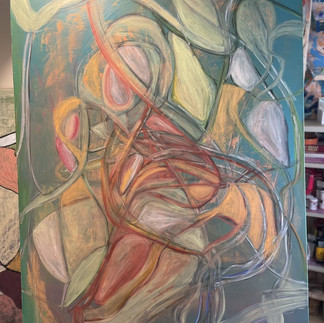

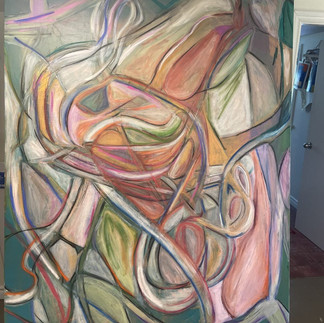

Visual creation comes in here — as a way of thinking without asking for immediate translation.

The image, the form, the color: all of it can carry what we don’t yet know how to say.

And it doesn’t have to make sense.

It doesn’t need technique.

It only needs a body.

The canvas, or any other surface, becomes a space of elaboration.

Not of an “ideal self,” but of what is in crisis, what craves movement.

Because what disturbs us — being a mother, not being one, being in doubt, feeling

out of place, exhausted, full of rage or fear — all of this is raw material for creation.

Living matter.

And as Rita Segato says, our subjectivity is constantly crossed

by the world’s violence.

But it can also be a place of invention.

To create is a way to reorganize the chaos.

To give shape back to what dominant language has disfigured.

Silvia Federici showed us that women’s bodies were expropriated — that capitalism began by seizing our capacity to generate, to care, to make with our hands.

And we were separated from our creative power precisely so we could become functional to the logic of accumulation.

So, when we express ourselves outside of that — outside the control of usefulness,

outside the logic of productivity — we’re already shaking the foundation of the structure.

To create, in this sense, is a gesture of autonomy.

It is also a form of care.

Maria Galindo speaks of an undisciplined feminism.

A feminism born from the ground, from contradiction, from error, from mixture.

Not from manuals.

But from real life. Creation is part of that: not as therapy, but as a practice of awareness.

As a mode of re-existence. The question then is no longer “how do I make something beautiful?”

It becomes:

what do I need to release right now?

what is asking to come through?

what is this discomfort trying to tell me?

What I propose here is a space where that is possible.

A place to create without the obligation to please, to explain, or to finish.

Without the rush of capitalist logic.

With time, with presence, with room for what is still becoming.

To express oneself, in this context, is also a way of forming thought.

And thought that is born from the body, from experience, from contradiction — is powerful.

Because it does not repeat.

It creates a crack.

And through that crack, the new can enter.

To paint is to remember,

to return to the body,

to return to oneself.

For so long, we were taught to be silent.

To silence rage, pleasure, doubt, desire.

To sever our own longing in order to fit into forms invented by others.

The regime of domination — which binds gender, race, and patriarchal power — amputated us from

our own center.

Separated us from our history, our feeling, our language.

But when a woman begins to narrate herself, something moves in the world.

To speak of oneself, as Rita Segato reminds us, is an act of insubordination.

It is to say: I was here.

I feel this way.

This touches me, disturbs me, shapes me.

And if to speak is to write with words, painting is to write with the body.

The canvas becomes confidante, mirror, shelter.

It doesn’t demand coherence.

It welcomes contradiction, fury, fatigue, and tenderness.

Silvia Federici showed us how capitalism intensified the patriarchal logic: separating us from the land, from the cycles, from other women, and from ourselves.

In painting, we undo that cut.

We create spaces where time is not productivity, but presence.

Where the gesture is not technique, but the language of the gut, of the viscera.

Where mistakes become paths and the stain becomes truth.

And then comes the question:

The uterus, that symbolic and real space — does it imprison or liberate you?

Perhaps it depends on who tells the story.

Perhaps, in art, we can relearn how to listen to that inner place.

To reclaim the body not as a territory of pain, but of creation/conscious invention.

Maria Galindo proposes a pedagogy that is born of lived experience.

A school without classrooms, where the curriculum is woven with affection, memory, revolt,

and dreams.

An embodied feminism, everyday, stained with paint, full of doubt, always in motion.

To paint, here, is not about aesthetics.

It is about existence.

About affirming that there is an intelligence in feeling, a philosophy in affection, a

politics in tenderness.

It’s about listening to discomfort —

because inside discomfort lives the question.

To be a mother, or not. To be Black, to be white, to be from the margins, to be trans, to be in

crisis.

All of this runs through us.

And what runs through us, also forms us.

And what forms us, needs a way out.

That’s why this practice of self-expression is not a luxury, nor a distraction:

it is a necessity. It is a way to sustain life in times of emptiness.

To create bonds where everything urges separation.

To return to oneself, not to isolate, but to be whole in the world —

ready to weave networks of support and sisterhood.

This space is for that.

To narrate oneself in color.

To say through image what language cannot yet reach.

To remember that we are protagonists of our own story —

we will not ask for permission.

Comments